The BlackBook: What Can We Learn From 1st-Generation Intel Processors?

Apple’s new computer chip, the M1 system-in-package processor, has taken the computer world by storm. The M1 can outperform many similar low power chips by Intel and even AMD while running in an emulation layer. This type of performance is unprecedented—but Apple’s CPU changes aren’t. They’ve gone from Motorola to the PowerPC coalition, from PowerPC to Intel, and they are now in the transition from Intel to “Apple Silicon.” What can we learn from these earlier transitions that apply to this one?

Apple’s switch from PowerPC to Intel is the most direct comparison. The company’s Power line of computers were performing well, but Intel’s chips were performing better. There is a key similarity here—the A13 Bionic in the iPad Pro regularly outperformed the base Intel i3 chip in the Macbook Air.

The key difference in the Intel transition was that Apple rebranded and redesigned their portable computers as “MacBooks,” as opposed to iBooks and PowerBooks. This hasn’t been the case so far. In fact, the external housings for the new Macbook Air, Macbook Pro, and Mac Mini are completely unchanged. As a result we can expect the design of these computers to be updated very soon, possibly with new 14” and 16” laptops that take advantage of the low-power Apple Silicon.

However, the most important thing to learn from these transitions is one key point: the second generation products always have more support than the first.

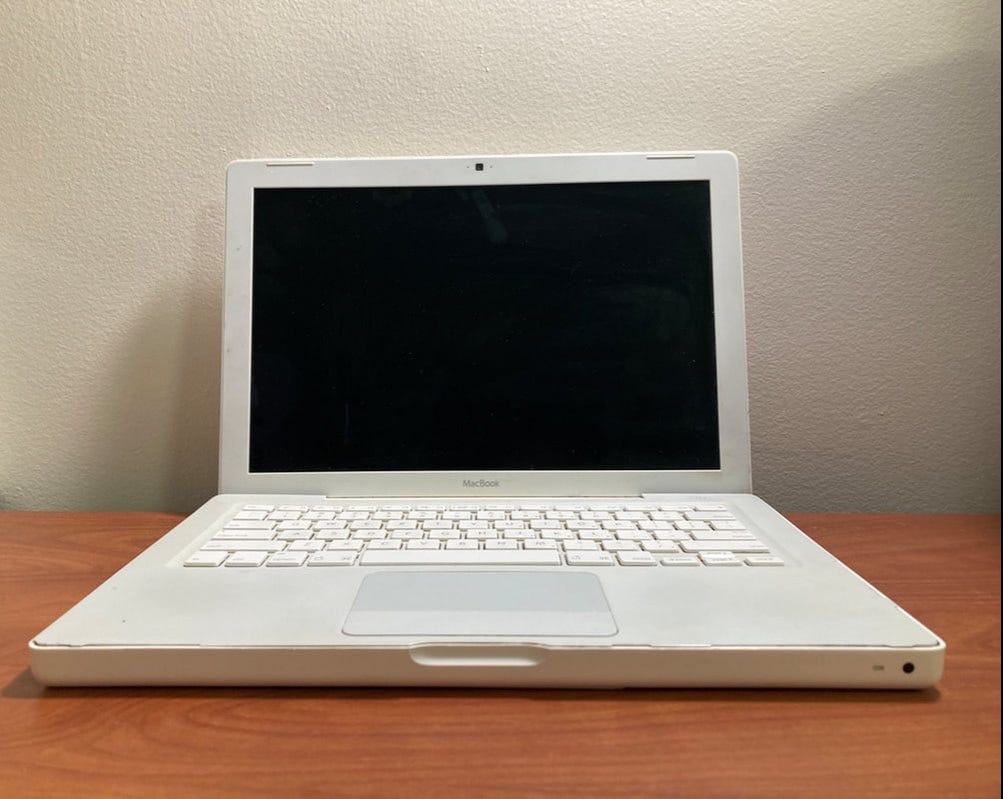

There is no better example of this than the transition to Intel, and thus, to MacBooks. The first ever Macbook, a glossy snow-white polycarbonate laptop, was released in early 2006 with an all-new Intel Core Duo processor. It was a massive improvement over the previous generation of PowerPC laptops. What followed was only one additional software update, and the original MacBook became obsolete in just a few years.

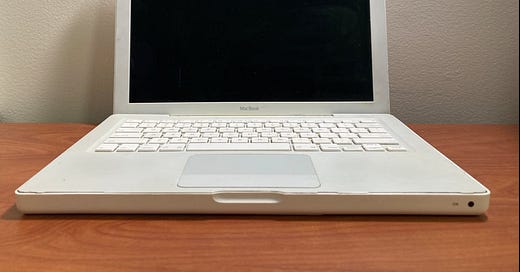

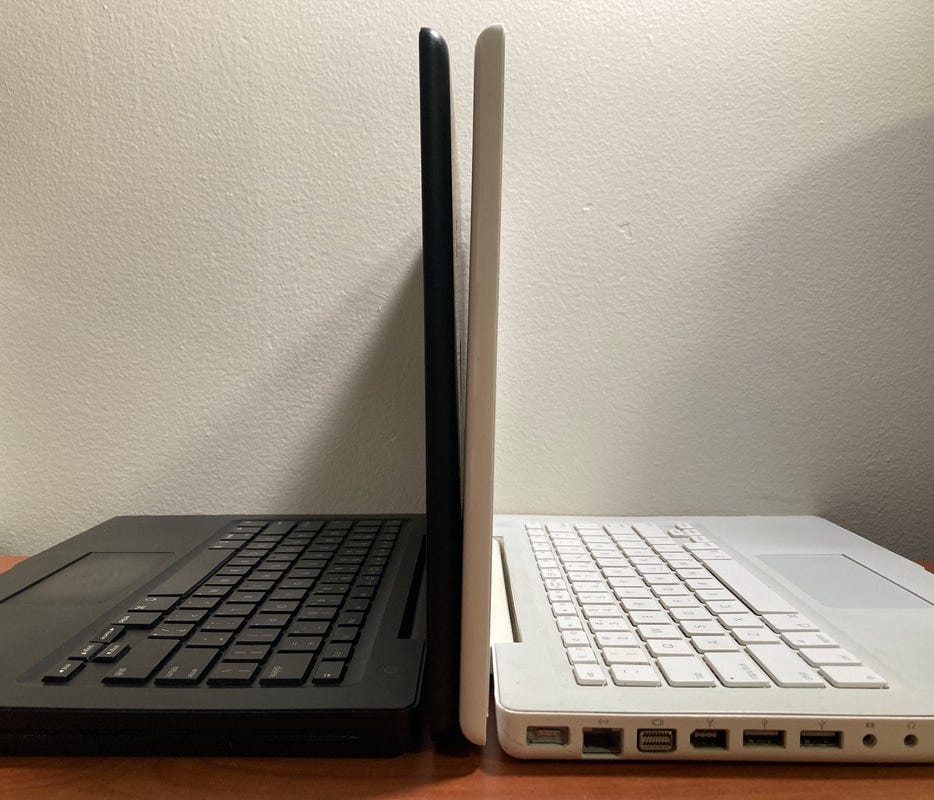

Just months later, Apple released the upgraded late 2006 models of the MacBook with Intel’s new Core 2 Duo processor, a dual core chip which greatly improved the machine. Two models were released: a glossy white polycarbonate MacBook and the only ever matte black MacBook, affectionately dubbed the “BlackBook.”

The new Core 2 Duo MacBooks received more software updates than the original MacBook despite being released just months later. The 2009 unibody MacBook can run MacOS 10.16 Catalina, a software update that was released ten years after the MacBook was released.

There’s a pattern here. Although the original MacBook (Intel) was groundbreaking at the time, it aged horribly. The BlackBook and new MacBooks aged better, but still became obsolete quicker than expected. The 2009 Macbook, released three years after the Intel transition began, can be patched to run the latest MacOS 11 Big Sur.

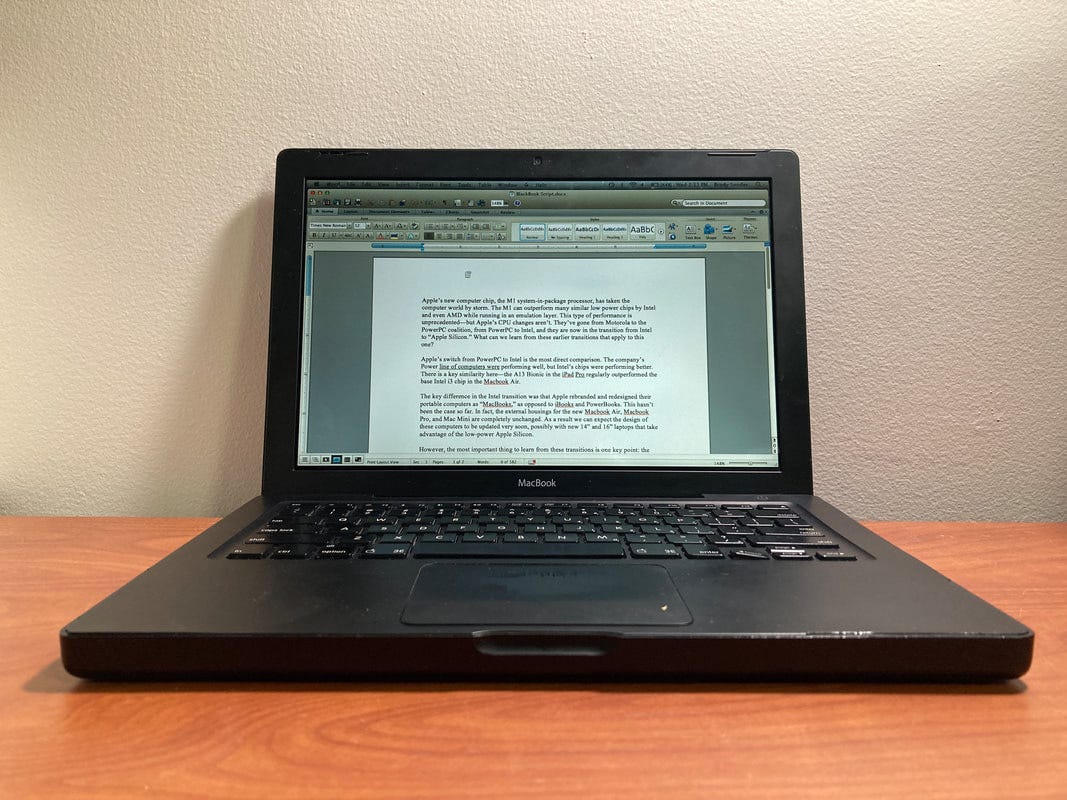

To learn from this history, we have to be cautious when purchasing new MacBooks. If you have to buy a new computer, you won’t be disappointed with a new M1 Mac. But if you don’t—and you’re just impressed by the M1’s performance—don’t buy it. The next Apple Silicon line of MacBooks will be significantly better than the M1, and the only proof that I need is that I am typing this entire article in Microsoft Word 2011 on the 2007 BlackBook.

Apple follows its history, and its patterns are known. The second generation MacBooks, iPads, iPhones, Apple Watches, and other Apple products have been significant improvements over the first. If you’re in awe of the M1, be in awe from afar—because something much greater is coming in the near future.